What happens to the sleep we didn’t get,

words we did not heed, or tears never allowed

to travel down our cheek?

Those weeks, or months,

you refuse to speak of; what happened?

Then.

What became

of the people we didn’t need, or like,

or replaced? Have you given any thought to

what you meant to them? Once upon a time

fairy tale or delusion.

Shared.

Then, remember

the personalities or prospects,

the ones where you didn’t have the self-respect

to introduce yourself to.

Where was your confidence,

or willingness to bare your soul?

Easier, is it not, to confide in a stranger?

Those familiar with your ways,

those who have read a few chapters of your story

may not understand

your reservation.

Someone back when

knew you well, wanted to know more,

then gave up.

Or was that you?

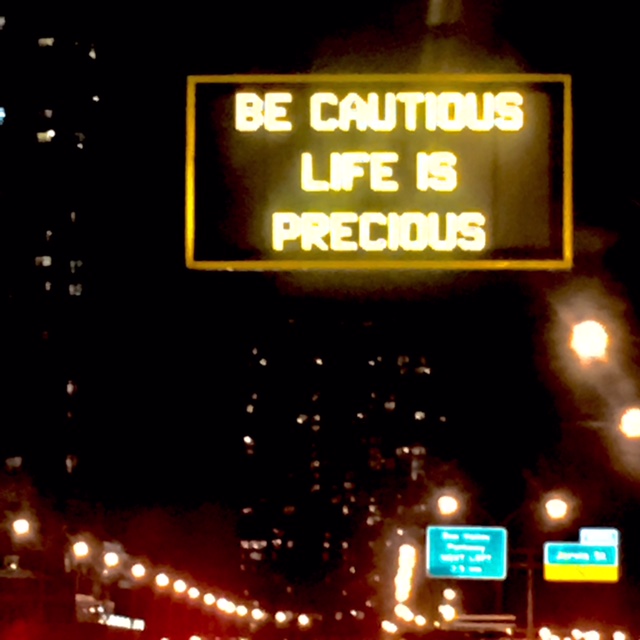

Emotions enrich our lives,

as easily as they can destroy

all we stay alive for.

Is that a reason to hold back?

There was once value in vulnerability.

Now; well, you know.

If you rephrase the question,

are the answers still the same?

Long past a series of coincidences,

the obscenity of silence remains.

© 2018 j.g. lewis