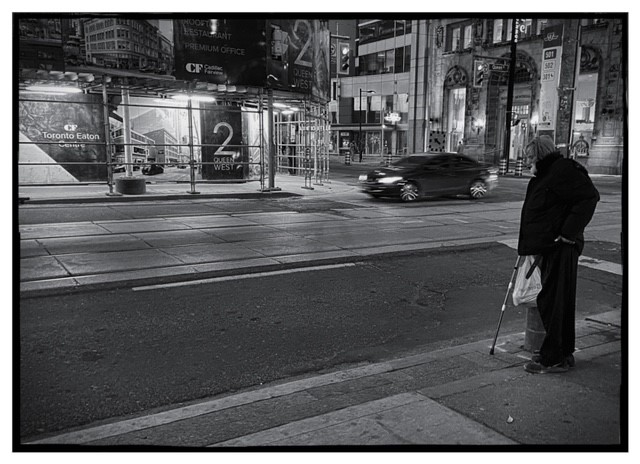

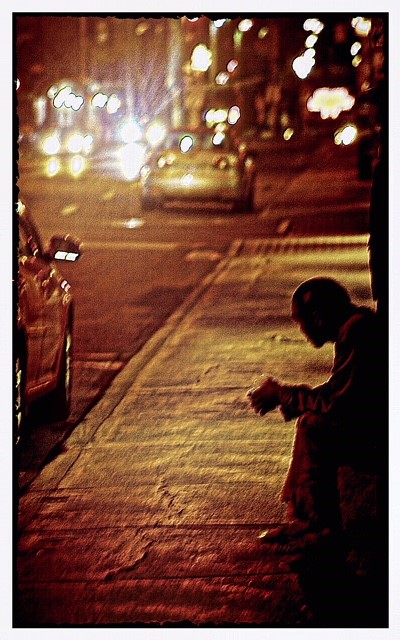

It’s shocking, but shouldn’t be, and sad for no other reason than of all the streets in Toronto, I am most familiar with Queen Street West.

I have no roots in this city but, after moving here five years ago, spent my spare moments of summer photographing the sights of Queen. It was a way of familiarizing myself with my new home.

I discovered Queen West is more than a street and far more than a neighbourhood. With all the shopping and dining, it is a street that seems to run 24-hours a day.

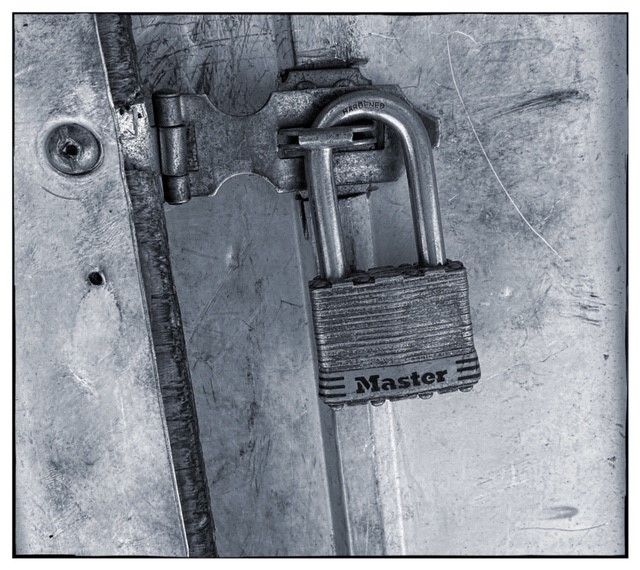

Except lately.

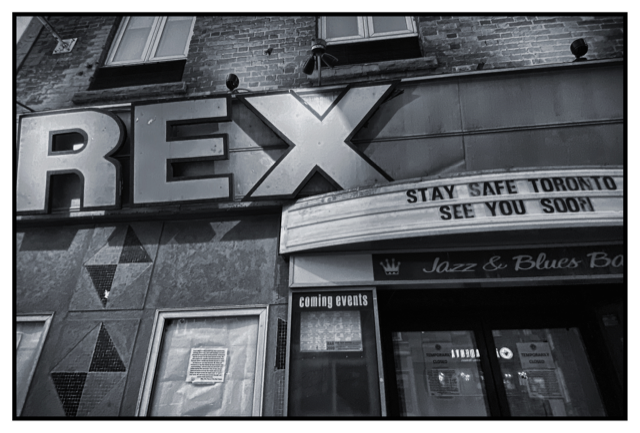

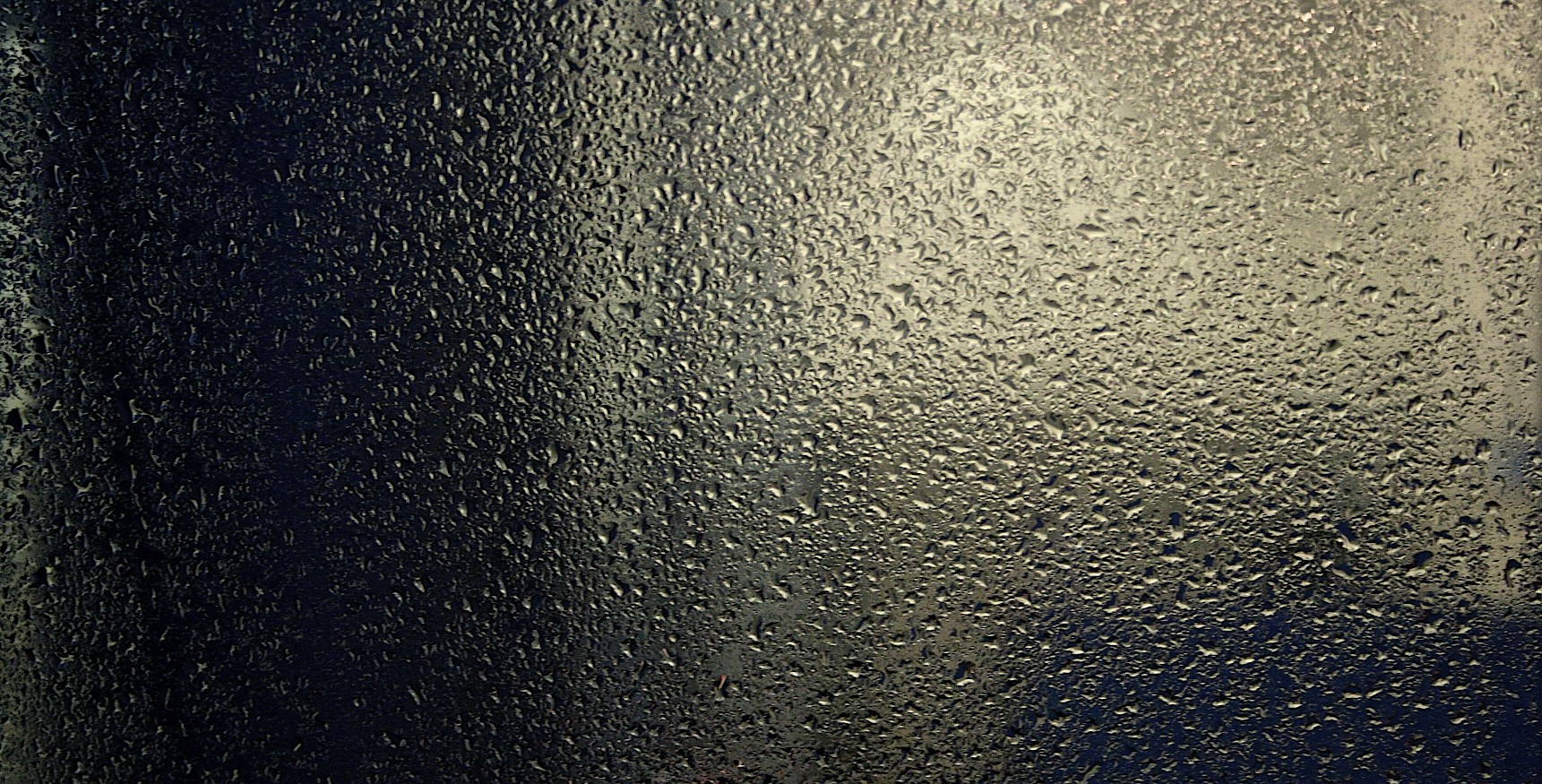

This street, like so many streets in Canada and beyond, is silent. The street is all but empty. Businesses locked down, storefronts are boarded up, and the restaurants that are open offer only take away. Parking is not a problem today.

It is not business as usual.

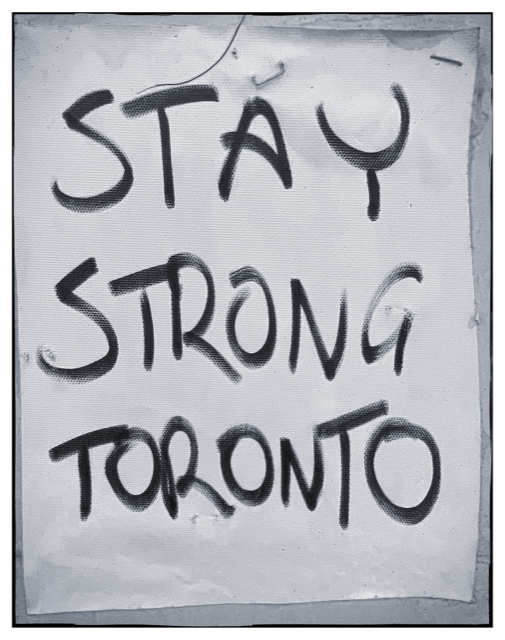

We don’t know how long this will last, but we know it needs time to heal.

This is not what we expected.

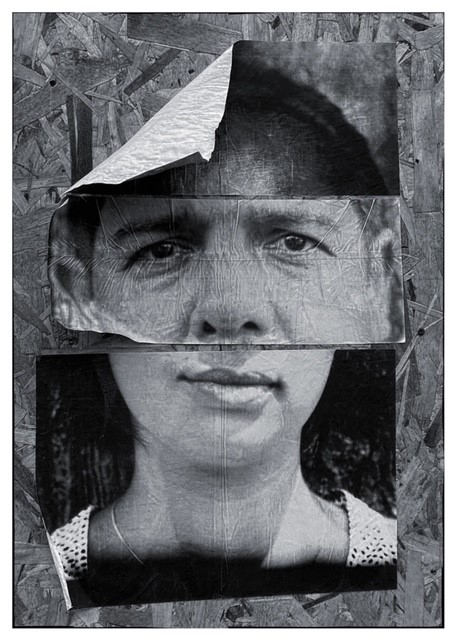

The face of the city is changing: it always has and always will.

How will we change with it?

click above for a look at Queen West five years ago